Scruples of Kurdish Political Elite under Scrutiny

M. R. Izady, 1994

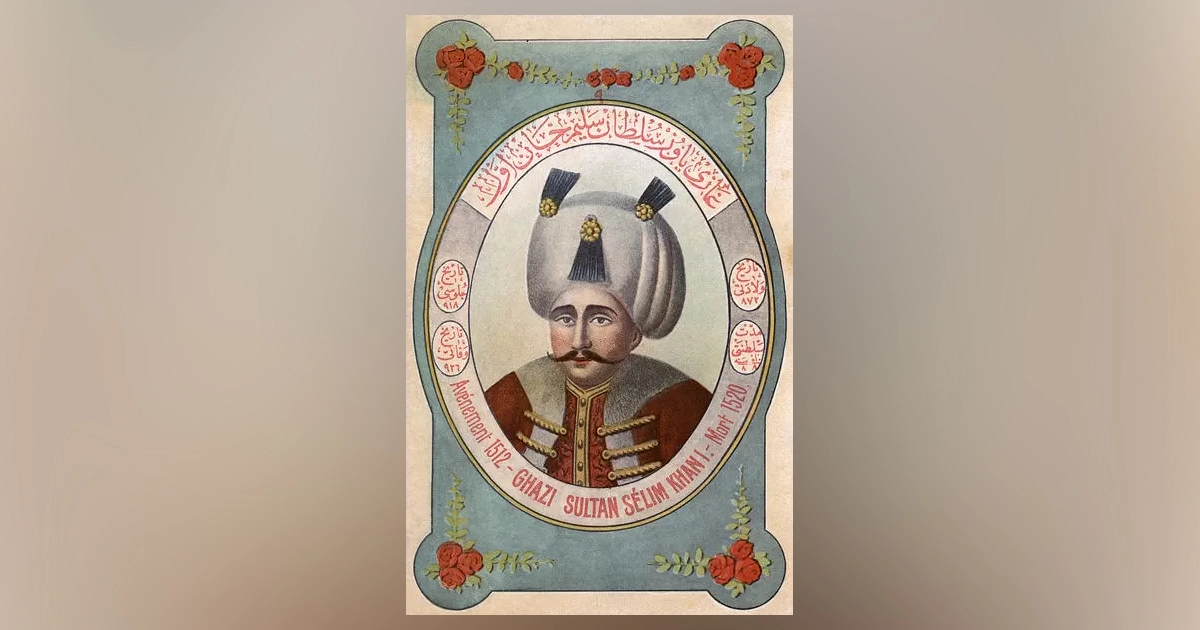

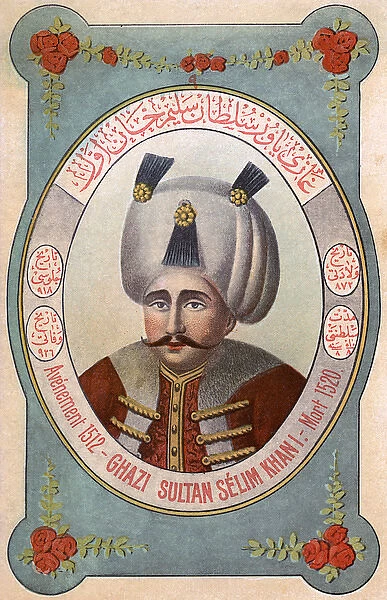

Limping back from the bloody Battle of Chaldiran against the Safavid Persians in 1514, the Ottoman Sultan Selim “the Grim” received Idris Bitlisi, a Kurdish man of great influence and diplomacy, but of little foresight. Idris had arrived to offer to deliver up Kurdistan to the Ottomans for a mere 25,000 gold ducats. Selim was delighted.

Unless sold from within, the sultan knew the fortress of Kurdistan could not be taken in any easy manner. All along, Idris thought he could outmaneuver the fox at Constantinople, by giving what he chose to give and deny what he determined to deny. The Kurd was soon proven wrong, and was reduced to a mere agent and spy for the Ottoman fox. Idris became the instrument of subversion for all independent Kurdish kings and prince in northern and western Kurdistan to the Turks: an occupation that continues to this day-- courtesy of Idris Bitlisi at the basement bargain price of 25,000 ducats.

At the time of delivering the goods, and true to his race, Idris asked for even less than what Selim was willing to give of cash or compliments. Heaping empty praises on Idris, in his lofty correspondence entitled, “The Imperial Edict of the Magnanimous Sultan,” Selim addresses the Kurd thus:

“To the chief of the wise, mentor of the virtuous, guide of the path of the holy laws, master of the Divine course, settler of religious disputes, solver of the dilemmas of faith, the essence of the mixture of water and clay [mankind], companion of the sultans and kings, the manifest of the monotheist worshipers, the master, Hakimaddin Idris, may God perpetuate his virtues.”

And what exactly were Idris’s virtues? They are the ones that many a Kurdish political leader today could easily correspond to: his eagerness to guard the interests of the outside powers—for the pragmatic reasons, no doubt—at the detriment of his own beleaguered nation. Little cash to pay for the trouble was, and is, also appreciated.

The buyer, Ottoman Sultan Selim, continues the address to Idris thusly:

“When this distinguished royal writ has arrived, you are to know that your letter has reached this Sublime Porte heralding the good news of being the liberating agent for the entire province of Diyarbakir.”

Idris had indeed ‘liberated’ western Kurdistan from the fellow Kurds and delivered it up to the Ottoman sultan. Selim is appreciative: “For your good faith and honesty, your intense friendship and openness, may God grant you joy and harmony. God the Almighty willing, you will be an active agent for liberating all those other provinces.” Idris did in time assume the post of ‘active agent’ assigned to him by the ‘Magnanimous Sultan,’ disarming and deceiving Kurdish kings and princes into submission to the enemy that still rules exactly those same parts of Kurdistan in 2003 which was delivered up by Idris in 1516--487 years ago. The price: 25,000 ducats.

Selim was not about to let go of such an industrious, not to mention inexpensive, agent. After arranging for the submission of his homeland to the Sultan, Idris is informed by Selim that he “should subsequently remain assured of every kind of our high royal thoughtfulness as you deserve.” But, the Kurd need not be spoiled with too much royal thoughtfulness and too fast.

To assure Idris’s continuous active agency, the Sultan dispenses the agreed sum only in small increments, and throws in some trinkets to consecrate the robbery.

“We have sent with your allowance for the period ending with the [lunar] month of Shawwâl, two thousand European gold florins, a sable coat and another of lynx, two woolen robes and two of broadcloth, also a cloak of broadcloth lined with sable; another with lynx, a gilded sword with a scabbard of European sheathing. The most generous God willing, you will receive these in much health and security and use them for your expenditures. I wish you to enjoy all that you deserve of our preeminent royal benevolence in appreciation for your services and as a reward for your unswerving loyalty.”

But, Selim coveted more, and Idris had to deliver up, now that he was well known for the ease of his scruples and the economy of his price. Casting the niceties of veiled suggestions and the pretence that Idris was anything but an agent selling his homeland, the Ottoman proceeds:

“Whereas you know the princes of Diyarbakir province, their circumstances, their friendship, loyalty, specialties and services and the titles and number of districts in your province, I have sent for your use blank royal writs, entitled with our blessed royal insignia, to the Governor-general of Diyarbakir, Muhammad.”

Thus compromised, eventually even open spying is demanded by the Porte from Idris:

“You are expected to write to the royal chancery at this Sublime Porte of the conditions of the autonomous districts that are allocated to each prince and how they are administered, titles of those princes, and the size of their fiefs as become appropriate. You are to record and send here for safe keeping all that need to be understood and clarified, such as a detailed memorandum about the autonomous districts given to princes, their authorities and how their titles are to be written. Also, the types of favor given to these, provided the dividing and designations do not violate the original agreement, so as to render it unlikely to disturb the foundations of their bonds to this Porte. I also send blank papers crowned with my cherished royal insignia to be sent to princes as is necessary to win their hearts. You dictate these letters of inclination as you see appropriate and send them with royal gifts and you record copies of those royal allocations and ways to tend to them in a special register and send it to this Porte, so every detail will be clear here. In this regard, the royal functions have been rendered complete to our esteemed desire upon those princes more than they expect.”

Selim’s deal with Idris is wrapped up by stating:

“In conclusion, we expect you to render all kinds of noble deeds and great feats. Be aware of this and place your trust in our esteemed royal insignia and this writ, issued in the middle of the month of Shawwâl of the hegira year of nine hundred twenty one [early November, 1515], at our Caliphal headquarters in Adrianople.”

Idris and his modern successors believe in the utility of pragmatism, and discard idealism. It is therefore an ironic coincidence that Idris Bitlisi was a contemporary of another, far more famous “pragmatist”: Niccolo Machiavelli (1469-1527). In his famed treatise, The Prince, Machiavelli gives chapter and verse on how an insider agent should be employed by a foreign aspirant to deliver up his native land. Neither Idris nor Sultan Selim had any knowledge of their illustrious Italian contemporary, but the knowledge of power and money, be it ducats or dollars, or the employment of the insider grandees to sell their own constituents is not something that needed or needs a Machiavelli to discover and introduce. It is a common proclivity in politics. Only the cash denominator has changed in the past 500 years, from ducats to dollars.

Dr. M.R. Izady,

New York, 1994 1st edition and 2003 2nd edition

1 The translation is from the text of Sultan Selim’s firman to Idris as it appears in Khwâja Sa’ad al-Din’s Tâj al-tawârikh (vol. 2, p. 322).