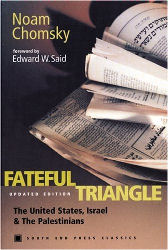

By Naom Chomski, " Updated Edition, June 1999"

One of the best books for Naom Chomski being updated it includes issues related to the Kurds.

For some time, I've been compelled to arrange speaking engagements long in advance. Sometimes a title is requested for a talk scheduled several years ahead. There is, I've found, one title that always works: "The current crisis in the Middle East." One can't predict exactly what the crisis will be far down the road, but that there will be one is a fairly safe prediction.

That will continue to be the case as long as basic problems of the region are not addressed.

Furthermore, the crises will be serious in what President Eisenhower called "the most strategically important area in the world." In the early post-War years, the United States in effect extended the Monroe Doctrine to the Middle East, barring any interference apart from Britain, assumed to be a loyal dependency and quickly punished when it occasionally got out of hand (as in 1956). The strategic importance of the region lies primarily in its immense petroleum reserves and the global power accorded by control over them; and, crucially, from the huge profits that flow to the Anglo-American rulers, which have been of critical importance for their economies. It has been necessary to ensure that this enormous wealth flows primarily to the West, not to the people of the region. That is one fundamental problem that will continue to cause unrest and disorder. Another is the Israel-Arab conflict with its many ramifications, which have been closely related to the major U.S. strategic goal of dominating the region's resources and wealth.

For many years, it was claimed the core problem was Soviet subversion and expansionism, the reflexive justification for virtually all policies since the Bolshevik takeover in Russia in 1917. That pretext having vanished, it is now quietly conceded by the White House (March 1990) that in past years, the "threats to our interests" in the Middle East "could not be laid at the Kremlin's door"; the doctrinal system has yet to adjust fully to the new requirements. "In the future, we expect that non-Soviet threats to [our] interests will command even greater attention," the White House continued in its annual plea to Congress for a huge military budget. In reality, the "threats to our interests," in the Middle East as elsewhere, had always been indigenous nationalism, a fact stressed in internal documents and sometimes publicly.

For many years, it was claimed the core problem was Soviet subversion and expansionism, the reflexive justification for virtually all policies since the Bolshevik takeover in Russia in 1917. That pretext having vanished, it is now quietly conceded by the White House (March 1990) that in past years, the "threats to our interests" in the Middle East "could not be laid at the Kremlin's door"; the doctrinal system has yet to adjust fully to the new requirements. "In the future, we expect that non-Soviet threats to [our] interests will command even greater attention," the White House continued in its annual plea to Congress for a huge military budget. In reality, the "threats to our interests," in the Middle East as elsewhere, had always been indigenous nationalism, a fact stressed in internal documents and sometimes publicly.

A "worst case" prediction for the crisis a few years ahead would be a war between the U.S. and Iran; unlikely, but not impossible.

Israel is pressing very hard for such a confrontation, recognizing Iran to be the most serious military threat that it faces. So far, the U.S. is playing a somewhat different game in its relations to Iran; accordingly, a potential war, and the necessity for it, is not a major topic in the media and journals of opinion here.

The U.S. is, of course, concerned over Iranian power. That is one reason why the U.S. turned to active support for Iraq in the late stages of the Iraq-Iran war, with a decisive effect on the outcome, and why Washington continued its active courtship of Saddam Hussein until he interfered with U.S. plans for the region in August 1990. U.S. concerns over Iranian power were also reflected in the decision to support Saddam's murderous assault against the Shiite population of southern Iraq in March 1991, immediately after the fighting stopped. A narrow reason was fear that Iran, a Shiite state, might exert influence over Iraqi Shiites. A more general reason was the threat to "stability" that a successful popular revolution might pose: to translate into English, the threat that it might inspire democratizing tendencies that would undermine the array of dictatorships that the U.S. relies on to control the people of the region.

Recall that Washington's support for its former friend was more than tacit; the U.S. military command even denied rebelling Iraqi officers access to captured Iraqi equipment as the slaughter of the Shiite population proceeded under Stormin' Norman's steely gaze.

Similar concerns arose as Saddam turned to crushing the Kurdish rebellion in the North. In Israel, commentators from the Chief of Staff to political analysts and Knesset members, across a very broad political spectrum, openly advocated support for Saddam's atrocities, on the grounds that an independent Kurdistan might create a Syria-Kurd-Iran territorial link that would be a serious threat to Israel. When U.S. records are released in the distant future, we might discover that the White House harbored similar thoughts, which delayed even token gestures to block the crushing of Kurdish resistance until Washington was compelled to act by a public that had been aroused by media coverage of the suffering of the Kurds, recognizably Aryan and portrayed quite differently from the southern Shiites, who suffered a far worse fate but were only dirty Arabs.

In passing, we may note that the character of U.S.-U.K. concern for the Kurds is readily determined not only by the timing of the support, and the earlier cynical treatment of Iraqi Kurds, but also by the reaction to Turkey's massive atrocities against its Kurdish population right through the Gulf crisis. These were scarcely reported here in the mainstream, in virtue of the need to support the President, who had lauded his Turkish colleague as "a protector of peace" joining those who "stand up for civilized values around the world" against Saddam Hussein. But Europe was less disciplined. We therefore read, in the London Financial Times, that "Turkey's western allies were rarely comfortable explaining to their public why they condoned Ankara's heavy-handed repression of its own Kurdish minority while the west offered support to the Kurds in Iraq," not a serious PR problem here. "Diplomats now say that, more than any other issue, the sight of Kurds fighting Kurds [in Fall 1992] has served to change the way that western public opinion views the Kurdish cause." In short, we can breathe a sigh of relief: cynicism triumphs, and the Western powers can continue to condone the harsh repression of Kurds by the "protector of peace," while shedding crocodile tears over their treatment by the (current) enemy.

Israel's reasons for trying to stir up a U.S. confrontation with Iran, and "Islamic fundamentalism" generally, are easy to understand. The Israeli military recognizes that, apart from resort to nuclear weapons, there is little it can do to confront Iranian power, and is concerned that after the (anticipated) collapse of the U.S.-run "peace process," a Syria-Iran axis may be a significant threat. The U.S., in contrast, appears to be seeking a long-term accommodation with "moderate" (that is, pro-U.S.) elements in Iran and a return to something like the arrangements that prevailed under the Shah.

How these tendencies may evolve is unclear.

The propaganda campaign about "Islamic fundamentalism" has its farcical elements — even putting aside the fact that U.S. culture compares with Iran in its religious fundamentalism. The most extreme Islamic fundamentalist state in the world is the loyal U.S. ally Saudi Arabia—or, to be more precise, the family dictatorship that serves as the "Arab facade" behind which the U.S. effectively controls the Arabian peninsula, to borrow the terms of British colonial rule. The West has no problems with Islamic fundamentalism there. Probably one of the most fanatic Islamic fundamentalist groups in the world in recent years was led by Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, the terrorist extremist who had been a CIA favorite and prime recipient of the $3.3 billion in (official) U.S. aid given to the Afghan rebels (with roughly the same amount reported from Saudi Arabia), the man who shelled Kabul with thousands killed, driving hundreds of thousands of people out of the city (including all Western embassies), in an effort to shoot his way into power; not quite the same as Pol Pot emptying Phnom Penh, since the U.S. client was far more bloody in that particular operation.

Similarly, it is not at all concealed in Israel that its invasion of Lebanon in 1982 was undertaken in part to destroy the secular nationalism of the PLO, becoming a real nuisance with its persistent call for a peaceful diplomatic settlement, which was undermining the U.S.-Israeli strategy of gradual integration of the occupied territories within Israel. One result was the creation of Hizbollah, an Iranian-backed fundamentalist group that drove Israel out of most of Lebanon. For similar reasons, Israel supported fundamentalist elements as a rival to the accommodationist PLO in the occupied territories. The results are similar to Lebanon, as Hamas attacks against the Israeli military become increasingly difficult to contain. The examples illustrate the typical brilliance of intelligence operations when they have to deal with populations, not simply various gangsters.

The basic reasoning goes back to the early days of Zionism: Palestinian moderates pose the most dangerous threat to the goal of avoiding any political settlement until facts are established to which it will have to conform.

In brief, Islamic fundamentalism is an enemy only when it is "out of control." In that case, it falls into the category of "radical nationalism" or "ultranationalism," more generally, of independence whether religious or secular, right or left, military or civilian; priests who preach the "preferential option for the poor" in Central America, to mention a recent case.

The historically unique U.S.-Israel alliance has been based on the perception that Israel is a "strategic asset," fulfilling U.S. goals in the region in tacit alliance with the Arab facade in the Gulf and other regional protectors of the family dictatorships, and performing services elsewhere. Those who see Israel's future as an efficient Sparta, at permanent war with its enemies and surviving at the whim of the U.S., naturally want that relationship to continue — including, it seems, much of the organized American Jewish community, a fact that has long outraged Israeli doves. The doctrine is explained by General (ret.) Shlomo Gazit, former head of Israeli military intelligence and a senior official of the military administration of the occupied territories. After the collapse of the USSR, he writes,"Israel's main task has not changed at all, and it remains of crucial importance. Its location at the center of the Arab Muslim Middle East predestines Israel to be a devoted guardian of stability in all the countries surrounding it. Its [role] is to protect the existing regimes: to prevent or halt the processes of radicalization and to block the expansion of fundamentalist religious zealotry." To which we may add: performing dirty work that the U.S. is unable to undertake itself because of popular opposition or other costs. The conception has its grim logic. What is remarkable is that advocacy of it should be identified as "support for Israel."

With some translation, Gazit's analysis seems plausible. We have to understand "stability" to mean maintenance of specific forms of domination and control, and easy access to resources and profits. And the phrase "fundamentalist religious zealotry," as noted, is a code word for a particular form of "radical nationalism" that threatens "stability."