The history of Judaism in Kurdistan is ancient. The Talmud holds that Jewish deportees were settled in Kurdistan 2800 years ago by the Assyrian king Shalmaneser Ill (r. 858-824 BC). As indicated in the Talmud, the Jews eventually were given permission by the rabbinic authorities to convert local Kurds. They were exceptionally successful in their endeavor. The illustrious Kurdish royal house of Adiabene, with Arbil as its capital, was converted to Judaism in the course of the 1st century BC, along with, it appears, a large number of Kurdish citizens in the kingdom (see Irbil/Arbil in Encyclopaedia Judaica). The name of the Kurdish king Monobazes (related etymologically to the name of the ancient Mannaeans), his queen Helena, and his son and successor Izates (derived from yazata, "angel"), are preserved as the first proselytes of this royal house (Ginzberg 1968, VI.412). But this is chronologically untenable as Monobazes' effective rule began only in AD 18. In fact during the Roman conquest of Judea and Samaria (68-67 BC), it was only Kurdish Adiabene that sent provisions and troops to the rescue of the beseiged Galilee (Grayzel 1968, 163)-an inexplicable act if Adiabene was not already Jewish (see Classical History). Many modern Jewish historians like Kahle (1959), who believes Adiabene was Jewish by the middle of the 1st century BC, and Neusner (1986), who goes for the middle of the lst century AD, have tried unsuccessfully to reconcile this chronolgical discrepancy. All agree that by the beginning of the 2nd century AD, at any rate, Judaism was firmly established in central Kurdistan.

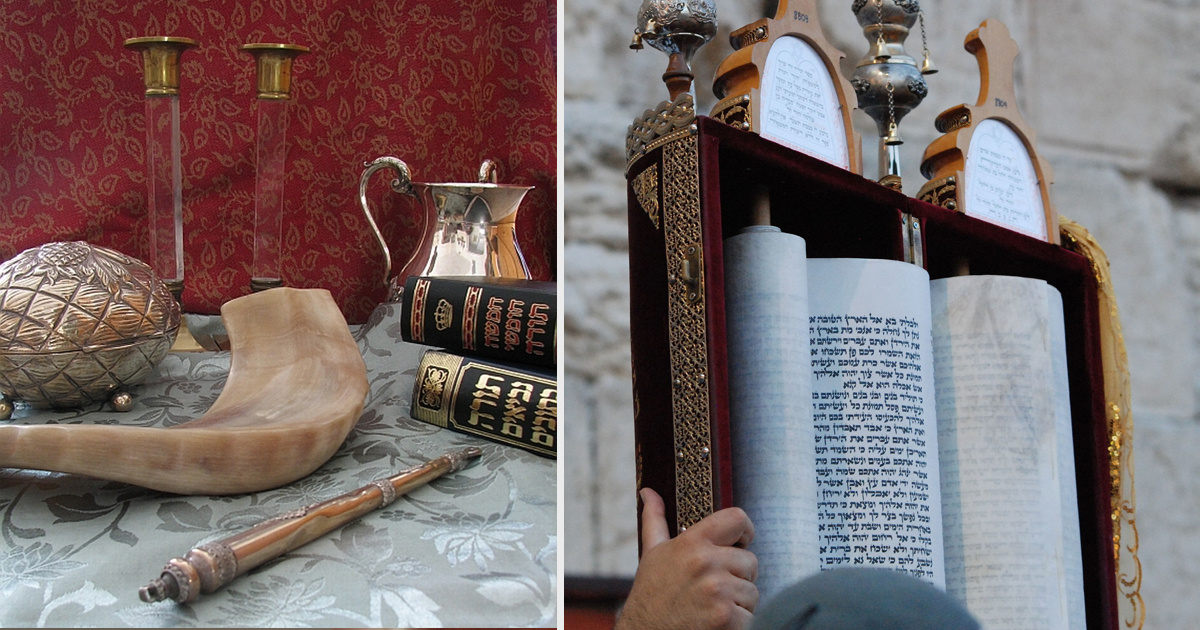

Like many other Jewish communities, Christianity found Adiabene a fertile ground for conversion in the course of 4th and 5th centuries. Despite this, Jews remained a populous group in Kurdistan until the middle of the present century and the creation of the state of Israel. At home and in the synagogues, Kurdish Jews speak a form of ancient Aramaic called Suriy,4ni (i.e., "Assyrian"), and in commerce and the larger society they speak Kurdish. Many aspects of Kurdish and Jewish life and culture have become so intertwined that some of the most popular folk stories accounting for Kurdish ethnic origins connect them with the Jews. Some maintain that the Kurds sprang from one of the lost tribes of Israel, while others assert that the Kurds emerged through an episode involving King Solomon and the genies under his command (see Folklore & Folk Tales).

The relative freedom of Kurdish women among the Kurdish Jews led in the 17th century to the ordination of the first woman rabbi, Rabbi Asenath B5rzani, the daughter of the illustrious Rabbi Samuel Bârzâni (d. ca. 1630), who founded many Judaic schools and seminaries in Kurdistan. For her was coined the term tanna'ith, the feminine form for a Talmudic scholar. Eventually, MAMA ("Lady") Asenath became the head of the prestigious Judaic academy at Mosul (Mann 1932).

The tombs of Biblical prophets like Nahum in Alikush, Jonah in Nabi Yunis (ancient Nineveh), Daniel in Kirkuk, Habakkuk in Tuisirkan, and Queen Esther and Mordechai in Hamadân, and several caves reportedly visited by Elijah are among the most important Jewish shrines in Kurdistan and are venerated by all Jews today.

The Alliance Isra6lite Universelle opened schools and many other facilities in Kurdistan for education and fostered progress among the Jewish Kurds as early as 1906 (Cuenca 1960). Non-Jewish Kurds also benefitted vastly, since children were accepted into these schools regardless of their religious affiliation. A new class of educated and well-trained citizens was being founded in Kurdistan. Operations of the Alliance continued until soon after the creation of Israel.

Many Kurdish Jews have recently emigrated to Israel. However, they live in their own neighborhoods in Israel and still celebrate Kurdish life and culture, including Kurdish festivals, costumes, and music in some of its most original forms.

Further Readings and Bibliography: Encyclopaedia ludaica, entries on Kurds and Irbil/Arbil; Louis Ginzberg, The Legends of the Jews, 5th cd. (Phdadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society of America, 1968); Jacob Mann, Texts and Studies in Jeu45/i History and Literature, vol. I (London, 1932); Yona Sabar, The Folk Literature of the Kurdi5tani Jews (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1982); Paul MagnareHa, "A Note on Aspects of Social Life among the Jewish Kurds of Sanandaj, Iran," Jwish Journal of SociologyXl.l (1969); Walter Fischel, "The Jews of Kurdistan," Commentary VIII.6 (1949); Andr6 Cuenca, "L'oeuvre de I'Aflance Isra6lite Universelle en Iran," in Les droits de I'dducation (Paris: UNESCO, 1960); Dina Feitelson, "Aspects of the Social Life of Kurdish Jews," jeiwsh Journal of Sociology 1.2 (1910); Walter Fischel, "The Jews of Kurdistan, a Hundred Years Ago," Jewish Social Studie5 (1944); Solomon Grayzel, A History of the Jews (New York: Mentor, 1968); Paul Kahle, The Cairo Geniza (Oxford, 1959); Jacob Neusner, ludaism, Christianity, and Zoroastrianism in Talmudic Babylonia (New York; University Press of America, 1986).

Sources: The Kurds, A Concise Handbook, By Dr. Mehrdad R. Izady, Dep. of Near Easter Languages and Civilazation Harvard University, USA, 1992