The early history of Christianity in Kurdistan closely parallels that of the rest of Anatolia and Mesopotamia. By the early 5th century the Kurdish royal house of Adiabene had converted from Judaism to Christianity. The extensive ecclesiastical archives kept at their capital of Arbela (modern Arbil), are valuable primary sources for the history of central Kurdistan, from the middle of the Parthian era (ca. 1st century AD). Kurdish Christians, like their Jewish predecessors, used Aramaic for their records and archives and as the ecclesiastical language.

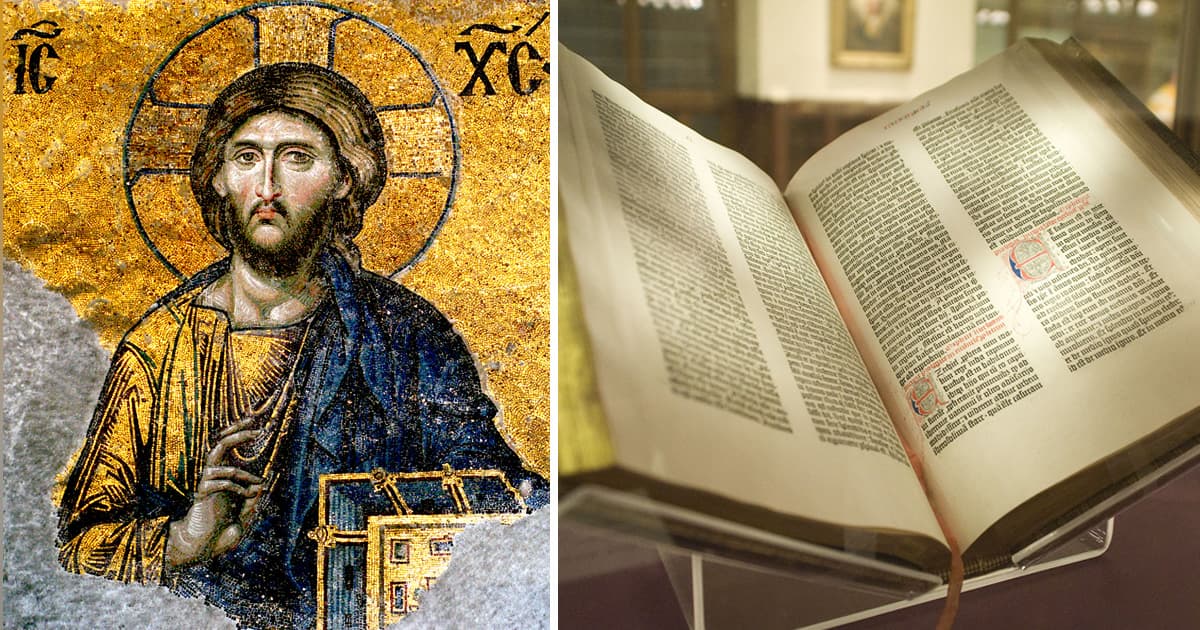

The persecution of the Christians in the Persian Sasanian Empire extended to Kurdistan as well. It was only after the conversion of the Empire's Christians to the eastern Nestorian church (from St. Nestorius, d. AD 440) and their break with Rome and Constantinople in the 6th century that they were given a measure of safety. At the time of the advent of Islam in the 7th century, central Kurdistan was predominantly Christian.

Anatolian Kurds, on the other hand, responded in two distinct manners to this new religion. The westernmost Kurds, i.e., those of Pontus and the western regions of Cappadocia and Cilicia in central and northern Anatolia, converted to Christianity before the 7th century. Their conversion, it turned out, was to cost them in the long run their ethnic identity. They were wholly Hellenized before the arrival of the Turkic nomads in Anatolia in the 12th century. The Kurds of eastern Anatolia, including eastern Cilicia and Cappadocia, and all those east of the Euphrates resisted conversion, and were punished for it by the Byzantines.

When in the 8th and 9th centuries the Byzantines deported and exiled the non-Christian populations from their Anatolian domain, Kurds suffered the most. The Cappadocian and Cilician Kurds were deported in toto (see Deportations & Forced Resettlements).

Christianity's effect on southern Kurdistan appears to have been marginal, but clear. The influence of Christian tenets on Yârsânism, which goes beyond the influences that would have been exerted via Islam, point to a direct exchange between the two religions.

With the waning and isolation of Christianity in Kurdistan and the Middle East following the expansion of Islam, the dwindling Christian Kurdish community began to renounce its Kurdish ethnic identity and forged a new one with its neighboring Semitic Christians. The Suriyâni (Nestorian) Christians of Mesopotamia and Kurdistan, who have recently adopted the ethnic name Assyrian, are a Neo-Aramaic-speaking amalgam of Kurds and Semitic peoples who have retained the old religion and language of the Nestorian Church, and the court language of the old Kingdom of Adiabene. A large number of these Suriyâni Christians lived, until the onslaught of World War 1, deep in mountainous northern Kurdistan, away from any ethnic or genetic influence of the Semitic Christians of lowland Mesopotamia. Their fair complexion, in marked contrast to that of their Semitic "brethren" in the Mosul region, also bears witness to their Kurdish origin.

Yet they speak Neo-Aramaic and insist on a separate ethnic identity. In the matter of language, the Christians in Kurdistan share the use of Neo-Aramaic with the Kurdish Jews.

Not all Christian Kurds found it necessary to exchange their Kurdish identity for their faith. The medieval Muslim historian and commentator Mas'udi reports Kurds who were Christians in the 10th century. In 1272 Marco Polo wrote, "In the mountainous parts [of Mosull there is a race of people named Kurds, some of whom are Christians of the Nestorian and Jacobite sects, and others Muhammadan" (Travels, I.vi). These are in fact Christian Kurds, as Polo earlier in his work distinguishes the non-Kurdish Christian population of the region.

There are records of missionary conversion of the Kurds to Christianity as early as the 15th century, a notable example being Father Subhalemaran (Nikitine 1956, 23 1). Many other missionaries have been sent from Europe and later America into Kurdistan since that time, with some of them producing the earliest studies of Kurdish language and culture, including dictionaries. Religious changes have almost always has entailed language change. Most Kurds who converted to Christianity eventually switched to Armenian and Neo-Aramaic, and were thus counted among these ethnic groups. A good example of this process was observed at the end of the World War 1.

At the time of the fall of the Ottoman Empire a considerable number of Christians who spoke only Kurdish left the area of western and northern Kurdistan for the French Mandate of Syria. There, having been told they "must be Armenian" if they were Christian, they were counted and eventually assimilated into the immigrant Armenian community of Syria and Lebanon.

Some non-Christian Kurds of Anatolia and even central Kurdistan still bless their bread dough by pressing the sign of the cross on it while letting it rise. They also make pilgrimage to the old abandoned or functioning churches of the Armenian and Assyrian Christians. This may well be a cultural tradition left with the Kurds through long association with Christian neighbors, or very possibly it stems from the time that many Kurds themselves were Christians.

Today there remain an uncertain number of Kurdish Christians, particularly in the districts of Hakkâri in north-central Kurdistan, Tur Abdin in western Kurdistan, and among the Milân and Barâz tribal confederacies in western Kurdistan in Turkey and Syria. In 1908 Sykes reports at least 500 Kurdish Christian families of the Pinianishli tribe in the Hakkâri district, whose leaders insisted they were an ancient community converted before the advent of Islam. Of the Hawerka tribe of Tur Abdin 900 families are listed as Christian, along with 700 more families from various other tribes in this region. Sykes is, however, silent on the number of MilAn Christians. Despite this, the question remains whether these and others are the modern descendants of the larger and more ancient Kurdish Christian community, or whether they are relatively recent converts by Christian Armenians, Assyrians, and Western Christian missionaries. Many centers for these recent proselytes were set up during the 19th and early 20th centuries in and around Bitlis, Urfa, Mosul, Urmih and Salmâs, to name a few. Likely, the Kurdish Christian population is an even mix of the ancient population and modern converts.

An educated guess for the total number of Christian Kurds (excluding the Assyrians, whose claim to a separate ethnic identity must be honored) would place them in the range of tens of thousands, most of them living in Turkey.

There is a renewed interest among the active Christian organizations in Europe, but par ticularly in the United States, to carry missionary work to Kurdistan. In fact, one of the first languages of the East into which the post-Renaissance Europeans translated the Gospel was Kurdish. New editions and new translations of the New Testament into North Kurmânji (Bshdinâni) are being attempted now. These translations and endeavors are targeted towards the Kurds in Turkey, as has been the case since the time of Father Subhalemaran.

The reason has been the faulty assumption of these missionary organizations that the Kurds of northern and western Kurdistan in Anatolia, having been under Byzantine rule prior to Muslim occupation, were mostly or all Christians, but that the other Kurds were not. The missionaries probably would find more fertile ground in central and part of southern Kurdistan, on the territories of the former Christian Kurdish kingdoms of Adiabene and Karkhu b't Salukh (Kirkuk), but not in northern and western Kurdistan, whose non-Christian inclinations made the Byzantines deport the populace in earlier times.

Further Readings and Bibliography: Asahel Grant, The Nestorians, or the Lost Tribes (London, 1841); Thomas Lauric, Dr. Grant and themountain Ne5torians (Cambridge, 1853); Helga Anschtitz, Die 5yrischen Christen vom Tor 'Abdin (Wiirzburg: Reinhardt, 1984); Michel Chevalier, Les montagnards chretiens du Hakkari et du Kurdistan septentrional (Paris: Department de Geographic de I'Universit6 de Paris-Sorbonne, 1985); John Joseph, The Nestorians and Their Muslim Neighbors (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1961); John Joseph, Muslim-Christian Relations and InterChristian Rivalries in the Middle East.. The Ca5e of the lacobites in an Age of Transition (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1983); G.P. Badger, The Nestorians and their Ritua15 (London, 1892); Marco Polo, Travels, ed. John Masefield (London: Dent, 1975); Basde Nikitine. "Les Kurdes et le Christianisme," Revue de I'Histoire des Religion (Paris, 1929); William Ainsworth "An Account of a Visit to the Chaldeans Inhabiting Central Kurdistan, and of an Ascent of the Peak of Rowandiz (Tur Sheikhiwa) in the Summer of 1840," Journal of the Royal Geographical Society XI (1941).

Sources: The Kurds, A Concise Handbook, By Dr. Mehrdad R. Izady, Dep. of Near Easter Languages and Civilazation Harvard University, USA, 1992