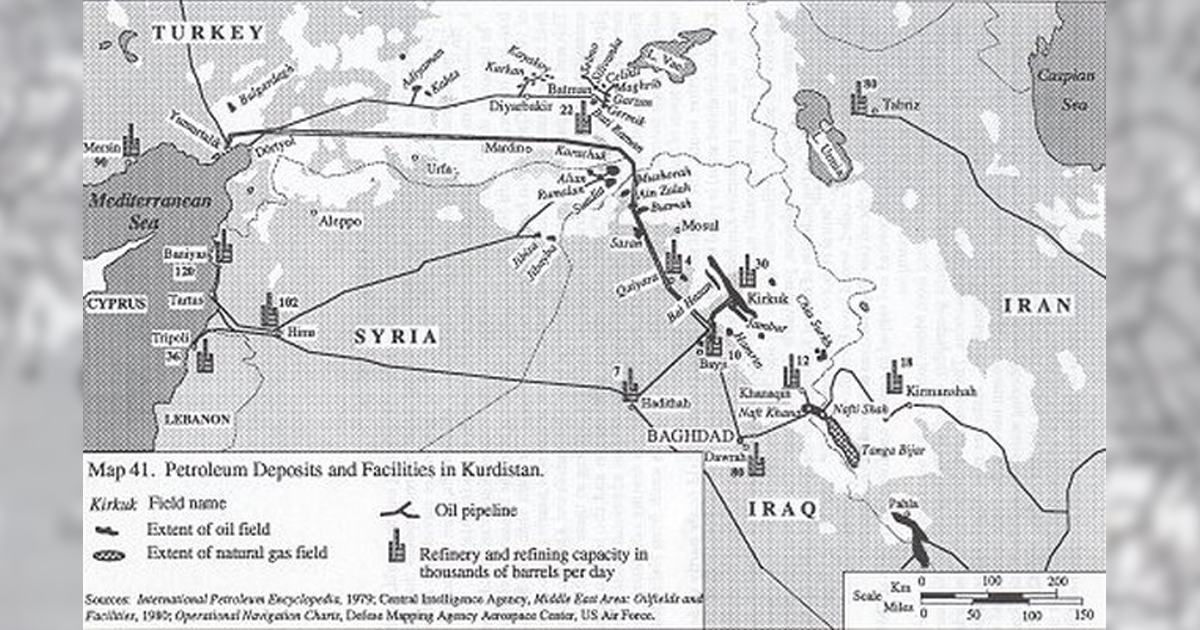

Kurdistan has among the largest oil reserves in the Middle East and the world. With about 45 billion barrels, Kurdistan contains more and larger proven deposits than the entire United States, and ranks 6th in the world. These reserves are spread over a thin band on the margins between the high mountains and the foothills, from far southern Kurdistan to extreme western Kurdistan near the Mediterranean Sea (see Map 41 below).

In the south, the fields of Nafti Shah-Naft Khana in far southern Kurdistan straddle the Iran-Iraq border. The Nafti Shah field (renamed Naft Shahr after the Iranian Revolution of 1979) near Qasri Shirin feeds a refinery in Kirmanshah. The Nafti Shah-Naft Khana field has been under production for over half a century and is now nearing exhaustion. This and the expansion of the refining capacities at both Kirmanshah and Khanaqin have necessitated the import of crude from other fields for refining at these facilities. A pipeline now connects the Kirmanshah refinery to Hamadan and the Iranian state network of oil pipelines. Likewise, the Khanagin facility receives additional crude from Kirkuk via a pipeline. While the Nafti Shah-Naft Khana field is nearing exhaustion, the adjoining rich natural gas field of Tanga Bijar, which stretches south from Nafti Shah toward the town of Sumar in Iran, has yet to be tapped.

Still farther south, the oil of the richer Pahla-Dehluran field (only partly under Kurdish-inhabited areas) is piped to Ahvâz and the Iranian ports on the Persian Gulf. By far the most productive Kurdish petroleum fields are at Kirkuk in central Kurdistan in Iraq. Oil here seeps naturally up to the ground and served as a source of bitumen and naphtha for ancient civilizations. Ignited by lightning, the natural fires there were venerated by various local religions, particularly Zoroastrianism. The Kirkuk fields were the principal reason for the inclusion of central Kurdistan into the British Mandate of Iraq (Nash 1976). Without this natural resource, it is almost certain that the Mosul Vilayet, as central Kurdistan was then called, would have been allowed to go to Kemalist Turkey-if they still wanted it without the oil. New fields are routinely discovered and tapped in central Kurdistan, with fields at Chia Surkh and Jambur being major examples.

A separate northern field stretching from Mosul into Syria has also been brought under production. This is the area the ancient geographer Claudius Ptolemy named Niphates Mons, i.e., the Naphtha (petroleum) Mountains. The productive fields on the Iraqi side of the area at Mushorab, Ain Zalah, Butmah, and Sâsân are now mostly tapped and joined to the main Iraqi pipelines. The Iraqi government has over the years constructed a vast network of oil pipelines, internally and in neighboring states. These include with Red Sea outlets at Yanbu in Saudi Arabia, Persian Gulf outlets at Mina al-Bakr and Khor alAmaya in Iraq, and Mediterranean outlets at Tartus in Syria and Dortyol-Yumurtalik in Turkey. The pipeline through Turkey has proven to be the most reliable and profitable in the past decade. With the Persian Gulf facilities destroyed in 1980, intermittently between 60% and 90% of all Iraqi oil exports passed through this single pipeline. After the opening of the Yanbu pipeline in 1986, this proportion stabilized at about 60% until 1991 and the total blockade of Iraqi oil exports. In the late 1980s, the pipeline became a double artery. It crosses almost exclusively Turkish Kurdistan all the way to the Mediterranean.

With the discovery of the giant oil fields of southern Iraq, the Kirkuk fields have also lost the vital importance they once had to the Iraqi state economy. While almost all Iraqi oil once came from Kurdistan, now only â third of the state's reserves are Kurdish. Kurdish fields in Iraq contain 36 billion barrels of reserves, out of â total of 90 billion barrels of proven reserves in all of Iraq. This development may in fact remove the strong objection of the central Iraqi government to sharing title to and revenues from the fields with the Kurds and various Kurdish autonomous local administrations which have been intermittently set up in central Kurdistan. It also may herald â time when Kurds will have even fewer valuable cards in their deck to bargain for economic and political concessions from Baghdad.

The same geologic formations that yield the Kurdish oil fields of Iraq north of Mosul continue on across the border into Syria in the Jazira region. The fields of Alian, Rumalan, Suadia, and Kara Chuk are now tapped, along with the Jubayba and Jibisa fields in the Sajar district farther south. Their yields are the only ones of note in Syria, and they are connected via â collecting pipeline to the Syrian heartland.

What little petroleum is produced in Turkey is from the Kurdish fields. The richest are in an area centered on the town of Bâtmân east of Diyârbâkir. Many small fields have been brought into production in the mountains around the town, and â collecting pipeline system brings the yield to the Bâtmân refinery. Another pipeline connects Bâtmân with the oil fields of Diyârbâkir, located in an arc north of the city. Farther west at Adiyâmân two primary fields have been brought under production and connected to the previous fields and facilities via another pipeline, and southwest to the port of Dörtyol on the Mediterranean.

So far Kurdish oil has not been produced in quantities large enough to satisfy the needs of the-internal market in Turkey, but promising formations continue to be prospected in this section of Kurdistan.

Further Readings and Bibliography: The International Petroleum Encyclopedia, 1979; Christopher Ryan, A Guide to the Known Minerals of Turkey (Ankara: Mineral Research and Exploration Institute of Turkey, 1960); I. Altin et al., Ölfekli Türkiye Jeoloji Haritasi ("Explanatory Text of the Geological Maps of Turkey"), sheets published loose at 1:500,000 scale for each Turkish province, accompanied by explanatory texts (Ankara: Mineral Research and Exploration Institute of Turkey, 1960-70); Middle East Area: Oil Fields and Facilities (Washington: U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, 1980), a sheet map at 1:4,500,000; Theodore Nash, "The Effect of International Oil Interests upon the Fate of Autonomous Kurdish Territory: A Perspective on the Conference at Sèvres, August 10, 1920," International problems 15, 1-2 (1976).

Sources: The Kurds, A Concise Handbook, By Dr. Mehrdad R. Izady, Dep. of Near Easter Languages and Civilazation Harvard University, USA, 1992